Grace & Free Will

Double predestination is a theological doctrine held

by traditional “hyper” Calvinists, which basically means God has willed to

create some people to be saved and others to be lost. In other words, human

beings cannot freely choose whether they want to be reconciled to God and be

saved or to reject God and risk losing their salvation. Their eternal destiny

is a predetermined fate that is beyond their control: spiritual as opposed to

biological determinism. This particular Protestant teaching rejects the idea

that our salvation partly depends on human desire and effort. It’s grounded on

the conviction that no one deserves God’s mercy because of their sins

and cannot merit their salvation by any natural means. This part is

true and acknowledged by Catholics, but Reformed Protestants of the classical

tradition even deny the idea of supernatural merit through the efficacy of

actual and cooperative grace.

These super-extreme Calvinists believe that, because

of our common sinful nature and original fall from grace, God can act with

partiality. God can choose the people whom He wills to be merciful to and those

whose hearts He will deliberately harden so that they cannot be saved. Hence,

human free will and supernatural merit within the system of cooperative grace

hold no place in this theological doctrine. Human beings are either formed of

clay for either a special purpose (the glory of God) or common use (for the

glory of God). Salvation, however, is no longer a merited gift or reward but an

undeserved favor (irresistible grace) only so that God can demonstrate His

omnipotence and mercy and consequently flaunt His divine will on a whim. There

is justice insofar as Christ’s alien righteousness is imputed to the believer

only because of their faith in His redeeming merits.

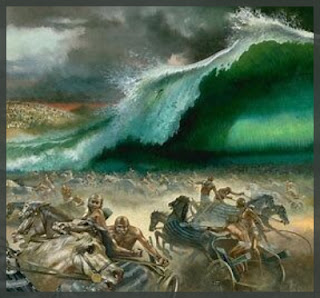

To support their belief system, hyper-Calvinists

usually cite Exodus 14 and Romans 9, which we will examine later since Paul

uses Pharaoh as an example for all the wicked. For now, let’s look at Exodus

and see whether it’s true that God has intentionally created some people for

eternal destruction, who, because of their sinfulness, can’t justly blame God

for His choice since God could have withheld His mercy from everyone if He so

chose – all having fallen short of the glory of God (Rom 3:23). Is the clay in

no position to argue with the potter? The answer is Yes but in a Catholic

sense. Can God justly show or withhold His mercy from whoever He chooses in His

sovereignty? Again, the answer is Yes, but in a Catholic sense.

But when Pharaoh saw that there was

relief,

he hardened his heart and did not heed them,

as the Lord had said.

Exodus 8:15

But Pharaoh hardened his heart at this

time also;

neither would he let the people go.

Exodus 8:32

And when Pharaoh saw that the rain, the

hail, and the thunder had ceased,

he sinned yet more; and he hardened his heart, he and his servants.

Exodus 9:34

Our non-Catholic friends fail to see what is actually

meant by the idea of God hardening one’s heart. They single out and isolate

Exodus 14 to support their preconceived notion formed from their

interpretation of other Scriptural passages in the New Testament. Chapter 14,

Verse 4 doesn’t mean that God somehow predetermined or molded Pharaoh from

wanting to release the Israelites from slavery. Rather, it means that God

permitted Pharaoh to remain unyielding to His command freely. Pharaoh,

unfortunately, was obstinate in heart. He refused to be persuaded even after

Egypt had been hit by several devastating plagues. In fact, because of his

pride, he grew even more intransigent after each plague was sent by God.

Pharaoh defied God and became even more defiant. God had hardened his heart,

but only because of the plagues, which resulted in its increased hardening.

Thus, Pharaoh grew even more defiant and unheeding with

each plague because of his pride. They boosted his ego, which influenced his decision to remain intransigent. In this way, God hardened his heart

by being physically responsible for sending the plagues. On the other hand, Pharaoh was morally responsible for them by his persistent disobedience to the divine command: “Let my people go!” God wouldn’t have commanded Pharaoh if he had no free will and choice in the matter. I’m afraid God doesn’t

mold us so that we should act against His will for the sake of His pleasure of

being merciful to a selected few other than ourselves and demonstrating how

merciful He can be when He wants to be by acting arbitrarily apart from our

desires rendering them moot.

On the contrary, God reveals His true intentions and

what he truly desires for everyone who is made of the same original clay through

the prophet: ‘Have I any pleasure at all that the wicked should die? says the

Lord GOD: and not that he should turn from his ways, and live?’ (Ezek 18:23;

cf. 1 Tim 2:3-4; 1 Jn 2:1-3; 2 Pet 3:9). The truth is God permitted Pharaoh to

become more obstinate of his own accord and then purposefully used his pride

and ego to free the Israelites from slavery in such an awesome way, as to

display His glory and might to the Egyptians.

14 What shall we say then? Is there

injustice on God’s part? By no means! 15 For he says

to Moses, “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion

on

whom I have compassion.” 16 So it depends not upon man’s will or exertion, but

upon

God’s mercy. 17 For the scripture says to Pharaoh, “I have raised you up for

the very

purpose of showing my power in you, so that my name may be proclaimed in all

the

earth.” 18 So then he has mercy upon whomever he wills, and he hardens the

heart of

whomever he wills. 19 You will say to me then, “Why does he still find fault?

For who can

resist his will?” 20 But who are you, a man, to answer back to God? Will what

is molded

say to its molder, “Why have you made me thus?” 21 Has the potter no right over

the

clay, to make out of the same lump one vessel for beauty and another for menial

use? 22

What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured

with much patience the vessels of wrath made for destruction, 23 in order to

make

known the riches of his glory for the vessels of mercy, which he has prepared

beforehand

for glory,

Romans 9

The basic principle embedded in Romans 9 is this:

Those who will not see and hear shall not see and hear. Consequently, God has

mercy upon whom he wills. He hardens whom he wills (cf. Jn. 9:41). In Vv.

14-16, Paul is simply affirming that there is no injustice on God’s part in not

granting what another has no natural right to (the forgiveness of their sins)

since all of us who have sinned justly deserve punishment. God isn’t indebted

to showing us His mercy in His justice. If, on the other hand, God shows His

mercy on some people, it is because of His goodness and liberality despite

their sins. If He leaves others in their sins (Pharaoh or the Pharisees) by

withholding his grace because of their stubbornness of heart, they are punished

for their just deserts.

God’s mercy shines upon His elect, those who are willing to receive His grace and open themselves to His word, but the divine justice is handed out to the wicked and the reprobate according to what they deserve through their moral liberty and obstinacy of heart. There is no just reason why God must show His compassion to those who refuse it. We cannot force our will on God and expect Him to be merciful to us while remaining in sin. Nor can we blame God for being sinful and punished for our sins by how we choose to act against His will.

No command of God is impossible for us to obey because we

have all received sufficient grace in our fallen condition. God’s efficacious

grace assists us in being righteous once we have directed our will to His

goodness. If we draw near to God, He will draw near to us and shower us with

His grace, not by any natural merit of ours because of our sinful state, but

through the sacrificial work of Jesus who has merited grace for us (Jas 4:8;

Heb 10:2, etc.). There are at least thirty-five Bible verses about drawing near

(not being drawn) by God, which presuppose we have free will and can either

accept or reject God’s merciful gift of salvation.

In v. 19, Paul responds to the objection that if God

rules over faith through the principle of divine election, God cannot accuse unbelievers of sin. The apostle, however, shows that God is far less

arbitrary than what might appear at first glance. He suggests in v. 22 that God

does endure with much patience people like Pharaoh who obstinately resist His

will. He reiterates why God might, without any injustice, have mercy on

some and not on others, grant particular graces and favors to His elect and not

equally to everyone. All humankind is liable to damnation, composed of sinful

clay, the state of original sin. No single soul has a just claim on the

Divine Mercy by any natural merit outside the system of divine grace.

So, those whom God chooses to remove from this sinful

lump to bestow His graces and favor are to display His

justice and hatred for sin. This is the underlying meaning in v. 23. God is

glorified by leading any of us to repentance by the riches of His kindness and

His mercy, which we mustn’t disregard if we hope to be saved according to the

divine plan (Rom 2:4). The “vessels of mercy” are those who by the grace of God

acknowledge their sins and repent with a firm desire for amendment with the

help of divine grace.

By leaving others as “vessels of wrath” that are lost

in their sins, Paul simply means that God has endured patiently as much as He

could, thereby abandoning them in their obstinate sinfulness and withholding

His grace and favor from them through their own intransigence and willfulness.

God knows the hearts of everyone, and so He knows who to touch and how to touch

their hearts so that they come to accept His will for them. Those who are

fettered by pride and selfishness are less likely to be drawn by divine

persuasion. God coerces no one, so He might decide to leave some people alone and in their sins while patiently waiting for them to change their hearts. He has already granted them the sufficient grace they need. Only those

who are humbly willing to align their wills with God benefit from His mercy by

answering the call and cooperating with his helping grace. These are the ones

who make every feeble effort to draw near to God with the help of His grace

that He will draw near to them. We can do nothing without God despite our

desire to be reconciled to Him, so we must ask for the graces we need and

will receive just by asking (Mt 7:7).

Hence, the allegory of the Potter and the Clay is by

no means intended to show that human beings are destitute of free will and

liberty, and so are completely passive in God’s plan of redemption, unable to

decide for themselves whether they want to be saved. It is used only to stress

that we are not to question God why He confers his graces and favors on some

and not on others since we are no better than each other in our sinfulness. If

there is any difference among us, some of us are humbler and less

proud by the grace of God and thereby most likely to acknowledge our sins and

be saved.

It is owing to the divine goodness and mercy that God

wills to create vessels of honor by His grace and gifts of the Holy Spirit. And

it is just that others because they refused to repent and convert, should

be given up as vessels of wrath undeserving of God’s mercy. Meanwhile, Paul’s

point is that God sovereignly decides whatever purpose He has for His elect

when bestowing His gifts of the Holy Spirit on them. God has a unique plan for

each of those who choose to love Him and obey Him, just as He has a plan for

those who choose to reject Him. It’s God and not any of us who takes the

initiative. But our collaboration is called for if we truly want to be saved

and come to the knowledge of the truth as God desires everyone to be (1 Tim

2:1-4).

Early Sacred Tradition

“And pray ye without ceasing in behalf

of other men; for there is hope of

the repentance, that they may attain to God. For ‘cannot he that falls arise

again, and he may attain to God.’”

St. Ignatius of Antioch, To the Ephesians, 10

( A.D. 110)

“And this is your condition, because of

the blindness of your soul, and the

hardness of your heart. But, if you will, you may be healed. Entrust yourself

to

the Physician [God], and He will couch the eyes of your soul and of your

heart.”

St. Theophilus, Bishop of Antioch, To Autolycus 7.

(inter A.D. 168-181)

“Now, in the beginning the spirit was a

constant companion of the soul, but the

spirit forsook it because it was not willing to follow. Yet, retaining as it

were a

spark of its power, though unable by reason of the separation to discern the

perfect, while seeking for God it fashioned to itself in its wandering many

gods,

following the sophistries of the demons. But the Spirit of God is not with all,

but, taking up its abode with those who live justly, and intimately combining

with the soul, by prophecies it announced hidden things to other souls.”

St. Tatian the Syrian, To the Greeks, 13

(A.D. 175)

“That eternal fire has been prepared for

him as he apostatized from God of his

own free-will, and likewise for all who unrepentant continue in the apostasy,

he now blasphemes, by means of such men, the Lord who brings judgment [upon

him] as being already condemned, and imputes the guilt of his apostasy to his

Maker, not to his own voluntary disposition.”

St. Justin Martyr, fragment in Irenaeus’ Against Heresies, 5:26:1

(A.D. 189)

“All indeed depends on God, but not so

that our free-will is hindered. ‘If then it

depend on God,’ (one says), ‘why does He blame us?’ On this account I said, ‘so

that our free-will is no hindered.’ It depends then on us, and on Him For we

must

first choose the good; and then He leads us to His own. He does not anticipate

our

choice, lest our free-will should be outraged. But when we have chosen, then

great is the assistance he brings to us…For it is ours to choose and to wish;

but

God’s to complete and to bring to an end. Since therefore the greater part is

of

Him, he says all is of Him, speaking according to the custom of men. For so we

ourselves also do. I mean for instance: we see a house well built, and we say

the

whole is the Architect’s [doing], and yet certainly it is not all his, but the

workmen’s also, and the owner’s, who supplies the materials, and many others’,

but nevertheless since he contributed the greatest share, we call the whole

his.

So then [it is] in this case also.”

St. John Chrysostom, Homily on Hebrews, 12:3

(A.D. 403)

“‘No man can come to me, except the

Father who hath sent me draw him’! For He

does not say, ‘except He lead him,’ so that we can thus in any way understand

that his will precedes. For who is ‘drawn,’ if he was already willing? And yet

no

man comes unless he is willing. Therefore he is drawn in wondrous ways to will,

by Him who knows how to work within the very hearts of men. Not that men who

are unwilling should believe, which cannot be, but that they should be made

willing from being unwilling.”

St. Augustine, Against Two Letters of the Pelagians, I:19

(A.D. 420)

Ask and it will be given to you; seek

and you will find;

knock and the door will be opened to you.

Matthew 7, 7

Pax vobiscum

.webp)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.png)